Forest: An Introduction

Why Hierarchies are Hard

From vector to unordered_map, container types serve to separate the details of the container from the data they maintain. C++ developers are no stranger to this valuable tenet. However, when it comes to hierarchical containers, we find ourselves without a generic go-to solution. At best, we’ll roll our own custom type for the specific use-case. At worst, that implementation embeds the hierarchy into the data itself. Who hasn’t seen something like the below, only to get nerd sniped in all the wrong ways as they have to maintain it?

template <typename T>

struct my_type {

my_type* _parent{nullptr};

my_type* _first_child{nullptr};

my_type* _next_sibling{nullptr};

T _my_actual_data;

}

What does it look like to enforce that your hierarchy is actually a hierarchy? What’s to stop a user of your container type from setting _first_child to _parent? How many squirrelly traversals do you need to do to assert that the user hasn’t embedded a cycle somewhere, somehow? The policing of such a structure becomes too expensive, and users are left to themselves to make sure they get things right. In the end, they are required to maintain the container’s consistency, which can be more expensive than maintaining the data itself. If a container type cannot maintain its own internal consistency, it fails a basic requirement of these types.

Easy Hierarchies: Beads on a String

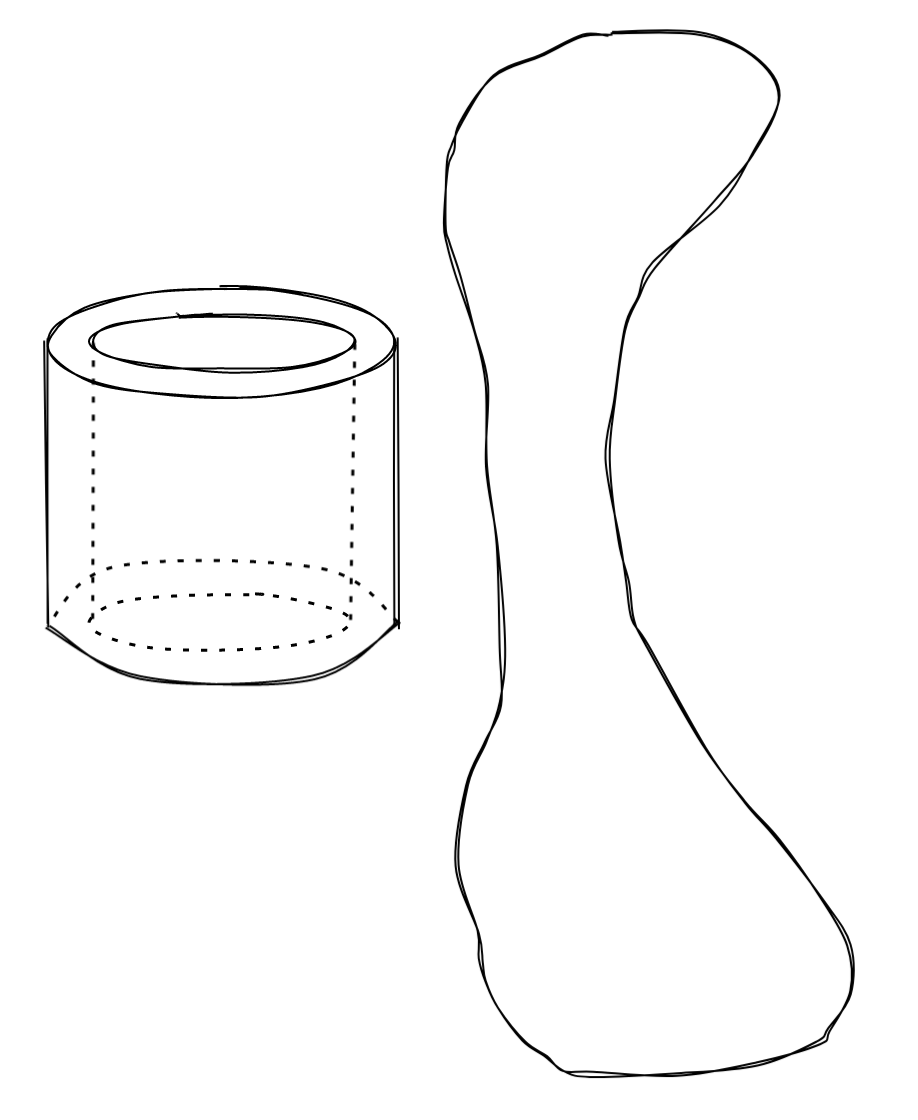

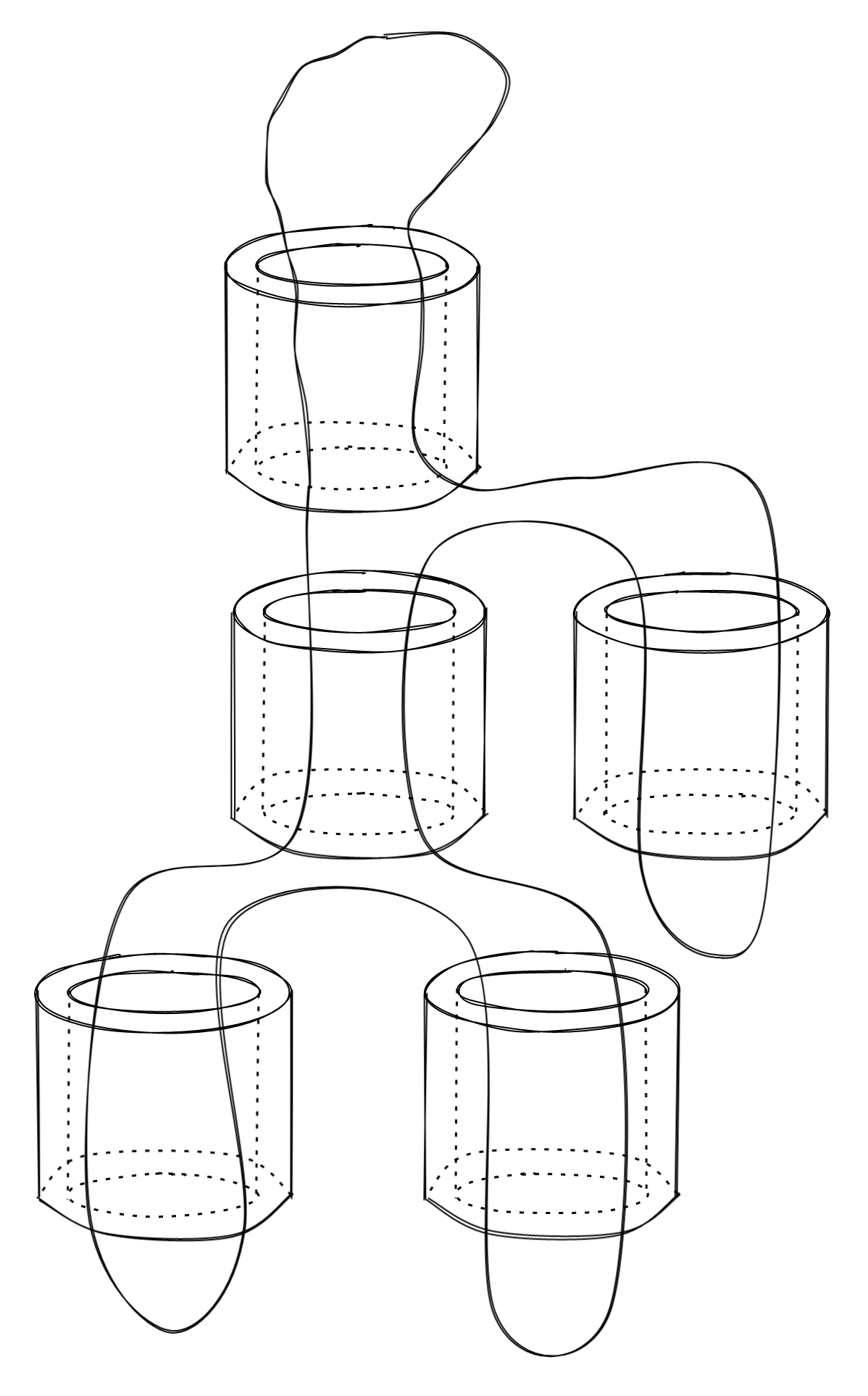

Let’s go back to childhood for a minute. Imagine if you will a bead with a hole through it and a bit of string that is tied to itself to form a loop:

It’s not hard to feed the string through the bead, giving you two loops of string that come out either side of the bead:

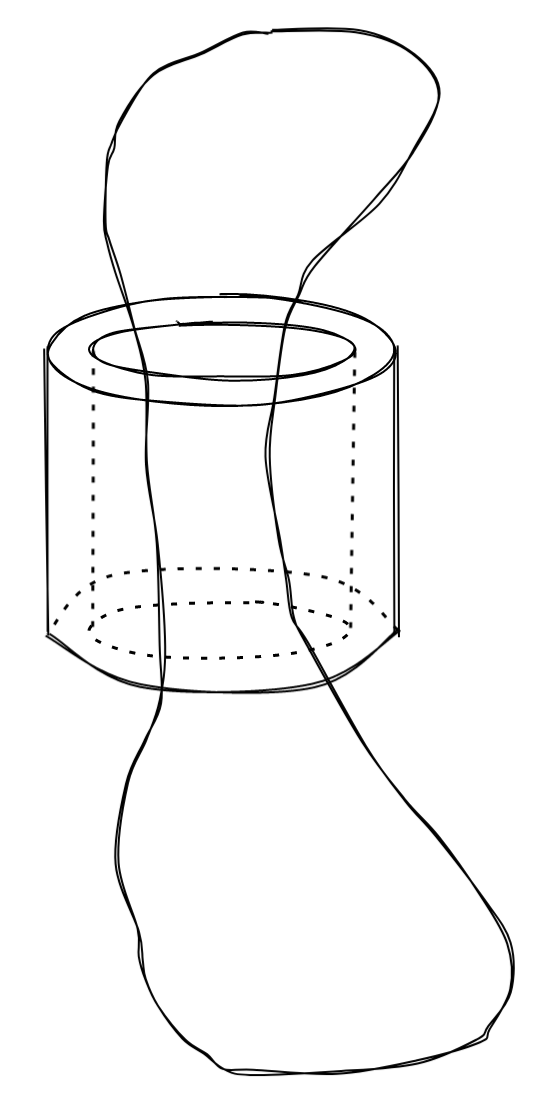

Feeding the string through another bead is easy enough, giving us the beginnings of some kind of necklace:

Now let’s add a third, but this time we feed it between the two beads we have. Since we have only been feeding the string through a bead once, we’ll keep following that rule:

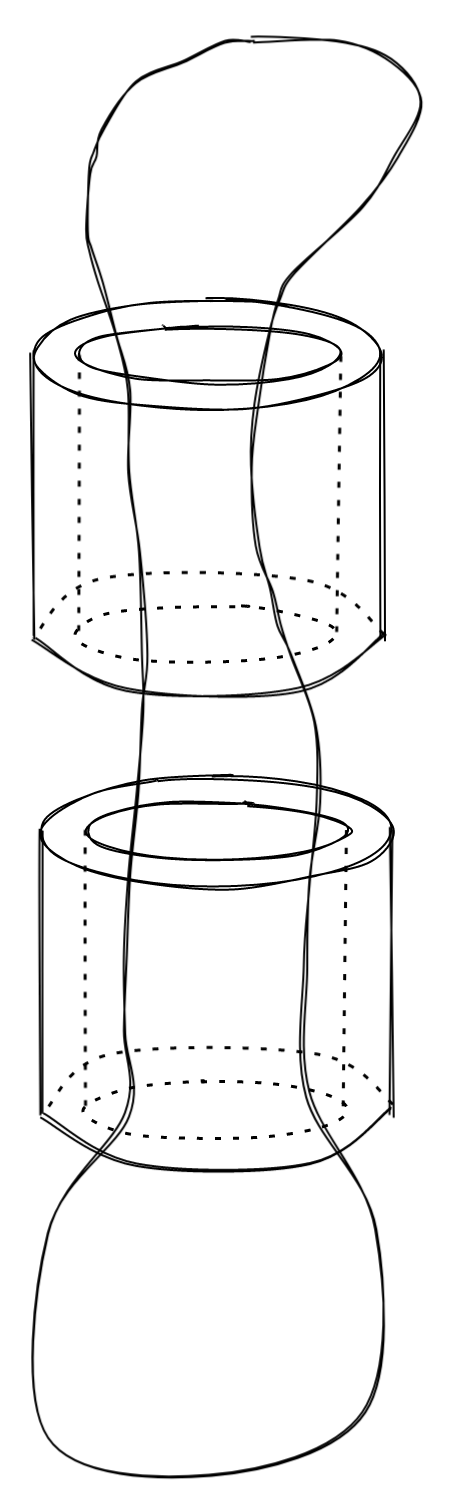

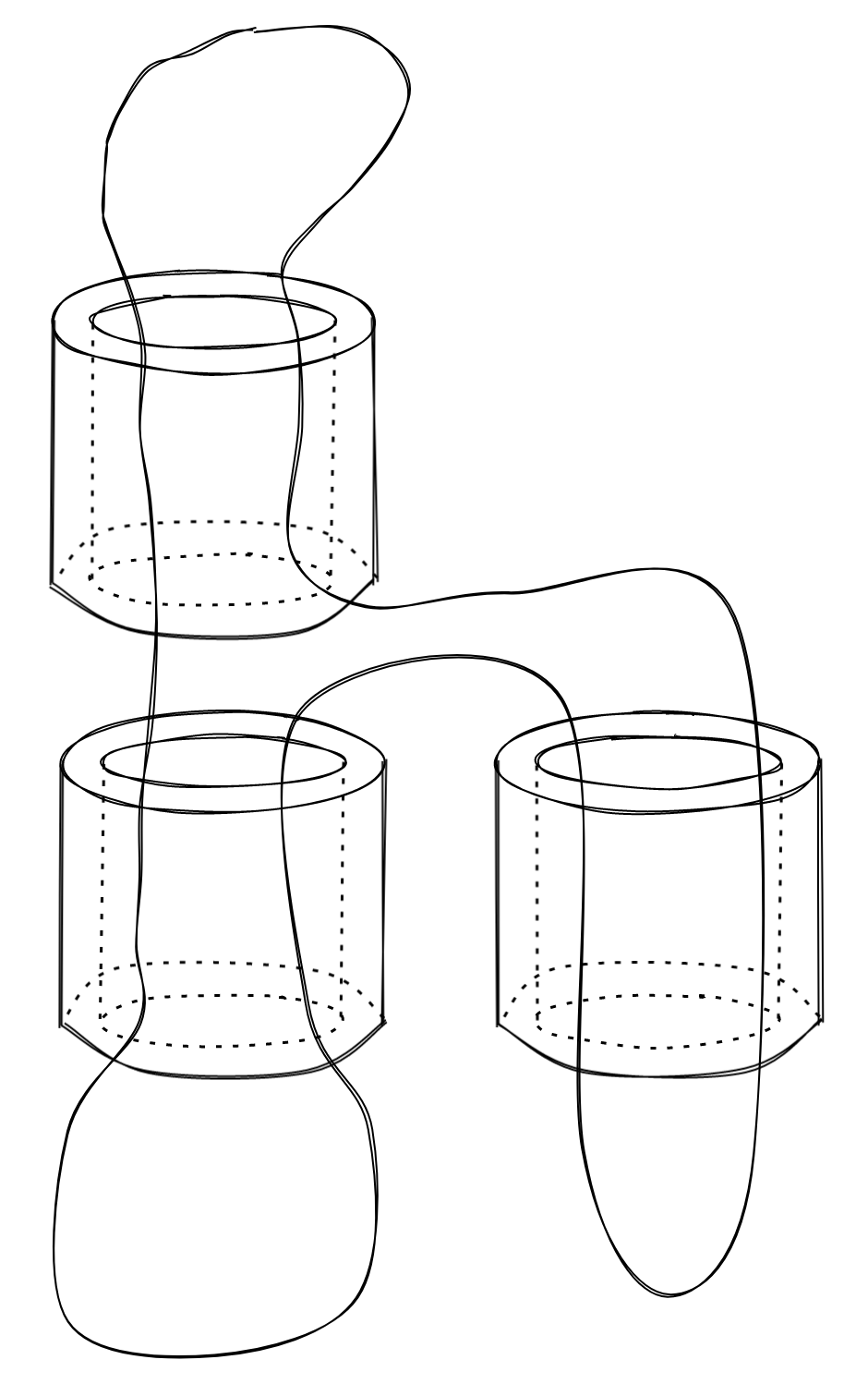

It turns out, if you follow the rule that the string can only be fed once through a bead, you cannot help but make a hierarchy. No matter where you add a new bead, you still have a hierarchy:

Enter the Forest

It is not a big step to transform our beads into nodes, and the loop of string into the edges between them. Sean Parent made this discovery many years back, spoke at length about it in a CppCon talk from 2015, and codified it into stlab::forest<T>. The remainder of this article will cover the high-level concepts of a forest, stlab::forest<T> implementation details, and a few examples. The next article will go more in-depth on an example that makes good use of forest.

The Root Node

Every forest has a root node, which is not a node used to store values in the forest. Rather, its primary purpose is as the anchor to which all top-level nodes in the forest are attached. (Going back to our childhood illustration, this is the case where all you have is the string.) Here, we will draw the root node as a rectangle:

Nodes

The forest’s value type is the node. They are heap-allocated as necessary for storing user data. Each node has exactly one parent, zero or more children, and zero or more siblings. Here, we will draw nodes as circles:

Edges

Forest nodes are connected by edges. For every node in the forest, there are always two edges that lead away from the node, and two that lead towards it. Here, edges are drawn as arrows pointed in the direction of forward travel:

The two left edges are known as leading edges, and the two right edges are known as trailing edges. (The terms come from the edges’ order of visitation during a full order traversal of the forest.)

The two edges that point to $N$ are known as in-edges and the edges that point away from $N$ are out-edges:

It is worth noting that the terms “in” and “out” are relative to $N$. In other words, an in-edge for $N$ will also be an out-edge for some other node.

Iterators

Forest iterators are bidirectional: although the diagrams are simplified by drawing one-way edges, in reality they are doubly-linked. Forest iterators come in forward, reverse, full order, preorder, and postorder flavors, and all are comprised of two pieces of data:

- The node ($N$) to which they point

- Whether they are on the leading ($L$) or trailing ($T$) edge of the node

Here, iterators will be described by this pair as {node, edge}. Since iterators always point to a node, we never speak of an iterator being on the out-edge of a node it is leaving. Rather, we always consider it on the in-edge of the node that it points to. Visually, iterators will only ever be on the northwest or southeast edge of the node to which they point.

An iterator pointing to the root node of a forest can be compared to other iterators in the same forest, but cannot be dereferenced.

Examples

{P, L}is an iterator that points to node $P$ on the leading edge:

{N, T}is an iterator that points to node $N$ on the trailing edge:

Iterator Advancement

While pointing at a node, there are always two ways an iterator could advance: the leading out-edge, or the trailing out-edge. The rule of thumb for iterator advancement is that iterators prefer the edge they are on. Thus, if an iterator is on the leading edge of a node, it will advance through the leading out-edge (and so for a trailing edge iterator.)

There are two specific cases where this rule does not hold. The first is on a leaf node, where the leading out-edge of the node arrives at the trailing in-edge of that same node. In this case, the iterator is flipped from leading to trailing. The second is when an iterator traverses from the trailing out-edge of a node to the leading in-edge of its next sibling. In this case, the iterator is flipped from the trailing to leading.

Edge Flipping

Utility functions stlab::leading_of(I) and stlab::trailing_of(I) change the edge of an iterator to leading or trailing, respectively. It does not matter what edge the iterator was originally on, and the iterator will still point to the same node. These are free functions, not members of stlab::forest<T>. In this document we will represent these routines in pseudocode as such:

leading_of({P, X})→{P, L}trailing_of({N, X})→{N, T}

In C++, these calls are straightforward:

stlab::forest<char> f;

auto leading_iter = f.insert(f.end(), 'A');

assert(leading_iter.edge() == stlab::forest_leading_edge);

assert(*leading_iter == 'A');

auto trailing_iter = stlab::trailing_of(leading_iter);

assert(trailing_iter.edge() == stlab::forest_trailing_edge);

assert(*trailing_iter == 'A');

A note on begin() and end()

begin() and end() in a forest behave just like their equivalent member functions found in a typical standard library container.

-

forest<T>::end()will always return{Root, T}. This is true regardless of whether or not the forest is empty. -

forest<T>::begin()will always return++{Root, L}. This follows the rules of the leading out-edge explained above, meaning that it will either point to the first node in the forest (if it is not empty), orend()(if it is).

Forest Edge Constraints

Now that we know about nodes, edges, and iterators, there are additional constraints the forest imposes upon its edges that maintain its structure. (Going back to our original illustration, these constraints make sure the string is only fed once through a bead.)

Leading In-Edge

Visually, the northwest edge is the leading in-edge. It originates (is an out-edge) from one of two possible nodes. First, if $N$ is the first child of its parent node $P$, this edge is the leading out-edge of $P$:

Otherwise, this edge is the trailing out-edge of $N$’s prior sibling $S_{prior}$:

Leading Out-Edge

The southwest edge is the leading out-edge. It terminates (is an in-edge) at one of two possible nodes. First, if $N$ is a parent, this edge is the leading out-edge of the first child of $N$, $C_{first}$:

Otherwise, this edge is the trailing out-edge of $N$ itself:

Trailing In-Edge

The southeast edge is the trailing in-edge. It originates (is an out-edge) from one of two possible nodes. First, if $N$ is a parent, it comes from the trailing out-edge of $N$’s last child, $C_{last}$:

Otherwise, it comes from the leading out-edge of $N$ itself:

Trailing Out-Edge

The northeast edge is the trailing out-edge. It terminates (is an in-edge) at one of two related nodes. First, if $N$ is the last child of $P$, this edge points to the trailing out-edge of $P$:

Otherwise, this edge points to the leading out-edge of $N$’s next sibling:

Example Forests

With the fundamental building blocks in place, here is how they combine to form some of the basic relationships in a forest. Note that every node in the forest maintains four relationships with the nodes around it.

The examples also include C++ that would construct the forest in question. If the code does not make sense right now, don’t worry: we’ll cover what’s missing in the following sections. If you’d like, you can skip over it now and revisit it later.

Empty

Given a forest that contains only the root node, forest<T>::empty() will return true. Otherwise, it will return false:

stlab::forest<int> f;

assert(f.empty());

The Root Top Loop

The root has a trailing out-edge which always points to its leading in-edge:

This “root top loop” is a unique property of the forest, and is used as a termination case in some traversals. For example, since preorder traversal iterators always point to a leading edge, the end iterator is the root top loop. (Because it is such a specialized implementation detail, the root top loop is often omitted when diagramming.)

One Node

To construct the above forest, the code might look like this:

stlab::forest<char> f;

f.insert(f.end(), 'A');

f.begin() would work equally well as f.end() in the above case. Like the standard containers, they are equal when a forest is empty.

Two Sibling Nodes

To construct the above forest, the code might look like this:

stlab::forest<char> f;

f.insert(f.end(), 'A');

f.insert(f.end(), 'B');

Many Nodes and Levels

stlab::forest<char> f;

auto a_iter = stlab::trailing_of(f.insert(f.end(), 'A'));

auto b_iter = stlab::trailing_of(f.insert(a_iter, 'B'));

auto c_iter = stlab::trailing_of(f.insert(b_iter, 'C'));

auto d_iter = stlab::trailing_of(f.insert(b_iter, 'D'));

f.insert(b_iter, 'E');

f.insert(c_iter, 'F');

f.insert(c_iter, 'G');

f.insert(c_iter, 'H');

f.insert(d_iter, 'I');

f.insert(d_iter, 'J');

f.insert(d_iter, 'K');

The frequent use of stlab::trailing_of is necessary to insert subsequent nodes as children of the newly inserted nodes. Without flipping the iterator to the trailing edge, new nodes inserted with those iterators would be added as prior siblings, not children.

Node Insertion

forest<T>::insert requires an iterator (where to insert) and a value (what to insert). The iterator is never invalidated during an insertion. insert returns a leading edge iterator to the new node.

Leading Edge Insertion

When the location for insertion is on the leading edge of $N$ (that is, $I$ is {N, L}) the new node will be created as $N$’s new prior sibling. So:

becomes the following. Note that the iterator is unchanged, still pointing to $N$ on the leading edge even after the insertion:

In this case insert returns {Sprior, L}. Leading edge insertion can be used to repeatedly “push back” prior siblings of $N$. To repeatedly “push front” prior siblings of $N$, use the resulting iterator of insert as the next insertion position.

Trailing Edge Insertion

When the location for insertion is on the trailing edge of $N$ (that is, $I$ is {N, T}) the new node will be created as $N$’s new last child. So:

becomes the following. Again, note that original iterator $I$ is unchanged after the call:

In this case insert returns {Clast, L}. Trailing edge insertion can be used to repeatedly “push back” children of $N$. To repeatedly “push front” children of $N$, use the resulting iterator of insert as the next insertion position.

Forest Traversal

Full order

The traversal behavior of stlab::forest<T>::iterator is always full order. This means every node is visited twice: first, right before any of its children are visited (on the leading edge), and then again after the last child is visited (on the trailing edge). This behavior is recursive, and results in a depth-first traversal of the forest:

In C++, one might output the above labels with the following code. The exception of course is 7, which cannot be output because it is the forest’s end() iterator.

stlab::forest<int> f;

auto n1 = f.insert(f.end(), 1);

f.insert(f.end(), 2);

f.insert(stlab::trailing_of(n1), 3);

std::size_t count = 0;

for (const auto& i : f) {

std::cout << ++count << '\n';

}

Here is the same diagram with the leading and trailing edges colorized green and red, respectively:

To output the “color” of the edges, one might write the following:

stlab::forest<int> f;

auto n1 = stlab::trailing_of(f.insert(f.end(), 1));

f.insert(f.end(), 2);

f.insert(n1, 3);

auto first = f.begin();

auto last = f.end();

std::size_t count = 0;

while (first != last) {

std::cout << ++count;

if (first.edge() == stlab::forest_leading_edge) {

std::cout << " green\n";

} else {

std::cout << " red\n";

}

++first;

}

Full order Traversal of $N$’s Subtree

To traverse a node $N$ and all of its descendants, the iterator range is:

leading_of({N, x})→first++trailing_of({N, x})→last

Note this technique does not work if $N==R$. In that case, you’d be traversing the entire forest, so you can use forest<T>::begin() and forest<T>::end().

Preorder Traversal

A preorder traversal of the forest will visit every node once. During preorder traversal, a parent will be visited before its children. We achieve preorder iteration by incrementing full order repeatedly, visiting a node only when the iterator is on a leading edge. Note the use of the root top loop as the terminating iterator for a full-forest preorder traversal:

Implementation

A C++ implementation of preorder traversal may look like this:

template <typename T, typename F>

void preorder_traversal(const stlab::forest<T>& forest, F&& func) {

auto preorder_next{[](auto i){

do {

++i;

} while (i.edge() == stlab::forest_trailing_edge);

return i;

}};

auto first{preorder_next(forest.begin())};

auto last{preorder_next(forest.end())};

while (first != last) {

func(*first);

first = preorder_next(first);

}

}

A better solution would be to use the preorder_range utility already provided by stlab::forest<T>:

for (const auto& i : preorder_range(my_forest)) {

// each node in the forest will be visited once, in preorder order.

}

Postorder Traversal

A postorder traversal of the forest will visit every node once. During postorder traversal, a parent will be visited after its children. We achieve postorder iteration by incrementing full order repeatedly, visiting a node only when the iterator is on a trailing edge:

Implementation

A C++ implementation of postorder traversal may look like this:

template <typename T, typename F>

void postorder_traversal(const stlab::forest<T>& forest, F&& func) {

auto postorder_next{[](auto i){

do {

++i;

} while (i.edge() == stlab::forest_leading_edge);

return i;

}};

auto first{postorder_next(forest.begin())};

auto last{forest.end()};

while (first != last) {

func(*first);

first = postorder_next(first);

}

}

A better solution would be to use the postorder_range utility already provided by stlab::forest<T>:

for (const auto& i : postorder_range(my_forest)) {

// each node in the forest will be visited once, in postorder order.

}

Child Traversal

A child traversal of a node P traverses only its immediate children; P itself is not visited. Child traversal is achieved by setting the edge of the iterator to trailing, then incrementing it:

++trailing_of({Cn, L})→{Cn+1, L}(next child) or{P, T}(the end of the range)

Implementation

A C++ implementation of child traversal may look like this. Note that the iterator passed points to the parent whose children we are going to traverse:

template <typename ForestIterator, typename F>

void child_traversal(ForestIterator i, F&& f) {

auto first{++stlab::leading_of(i)};

auto last{stlab::trailing_of(i)};

while (first != last) {

f(*first);

first = ++stlab::trailing_of(first);

}

}

A better solution would be to use the child_range utility already provided by stlab::forest<T>:

for (const auto& i : child_range(my_forest_iterator)) {

// each child of the node at my_forest_iterator will be visited once

}

To iterate just the top-level nodes in the forest, use stlab::forest<T>::root() to get an iterator to the root node:

for (const auto& i : child_range(my_forest.root())) {

// each top-level node will be visited once

}

Erasing Nodes

Like most STL containers, erasing nodes in a forest starts by passing two iterators denoting the range to erase. The rule for deleting forest nodes is this: a node will be erased if and only if the deletion traversal passes through that node twice. The nodes to be erased from the forest are always processed bottom-up. This means that a parent’s child nodes will always be deleted before the parent. It also means that all nodes will be leaf nodes at the time they are erased.

Erasing Example

Consider the following forest and the defined first and last iterators into that forest for erasing:

Initially, the iterators are at {B, L} and at {R, T}. The nodes $B$ and $C$ will be deleted because the traversal from first to last will go through each of those nodes twice. Even though the deletion iterator will pass through $A$, it is not deleted because it only passes through on the trailing edge, not on the leading edge:

After the above erase has completed, the resulting forest will be:

Conclusion

Containers should make a developer’s life easier, not harder. When a container type requires you to think about maintaining its validity, it fails to achieve that intent. Forests present one solution to the hierarchy container type that is internally consistent. By maintaining itself, a forest lets you get back to handling the data, instead of the container.

The Sources

“Enough already,” you cry, “show me the sources!” stlab::forest<T> is maintained as part of the Stlab Library, and is available on GitHub. We also have documentation for the class, as well as utility data structures and forest algorithms.